Galli Uhren Bijouterie AG

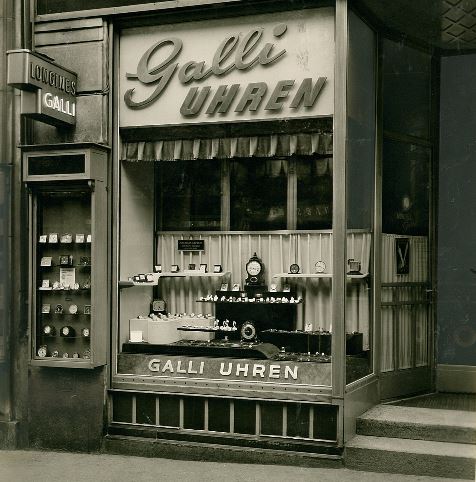

Theaterstrasse 16, on Bellevue

CH-8001 Zurich

Tel: +41 44 262 04 10

Fax: +41 44 252 49 96

Galli family oral tradition has it that the “Galli” came from Italy. At the beginning of the 19th century, when today’s Italy was still divided into four kingdoms, Fernando Galli is said to have been recruited from the Kingdom of Italy for Napoleon’s 1812 Russian campaign. This Fernando was one of the few who made it back alive across the Berezina during the retreat and then settled in Germany, at Königsberg in eastern Brandenburg (Chojna, Poland since 1945.)

Fernando Galli is said to have been recruited from the Kingdom of Italy for Napoleon’s 1812 Russian campaign

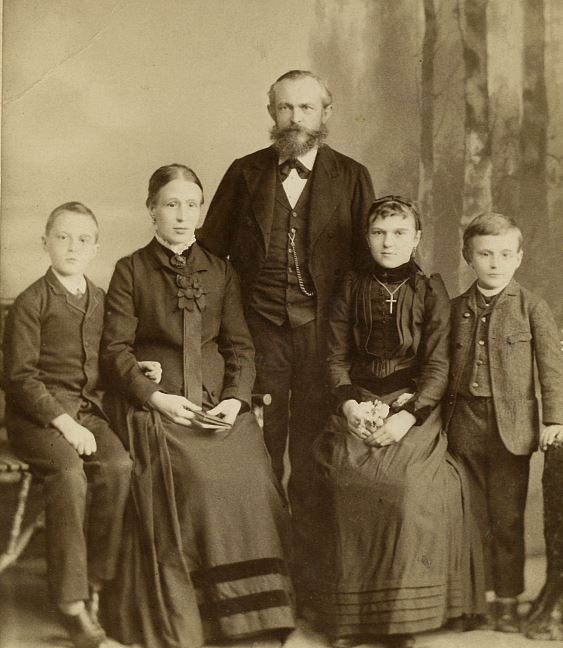

Paul Galli came into the world in Königsberg on December 2, 1859. He learned watchmaking in the house next door, presumably in the watch shop owned by Louis Futter. His apprenticeship, during which he had to wind the entire town’s public clocks including the tower clock on St. Mary’s church, lasted from 1874 to 1877.

With his schooling behind him, he began his years as an itinerant watchmaker. As was still customary in those days, these were journeys made on foot. When the money ran out, he would hire on as a watchmaker at any place along his itinerary that he could. Wherever he hired on, the local mayor would personally sign his certificate.

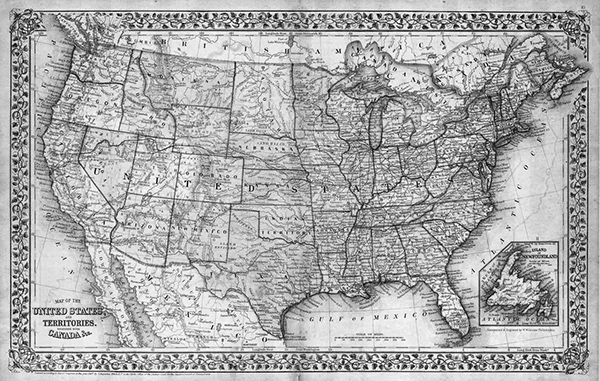

When he had enough money in his pocket again, he would resume his wanderings, usually in the company of other itinerant apprentices. He crisscrossed Germany, wound up on the seacoast and from there he crossed over to North America. He worked off his passage as a coal shoveler. After a stay in Pittsburgh, he returned to Europe in the same manner. He went up the Rhine by way of Cologne and Heidelberg until he reached Basel. Then it was on to Geneva, to Chur in northern Italy and a few places in the Swiss canton of Grisons. Then, back once more in Germany, Paul worked in Munich and Altomünster, Bavaria. It was at this time that he was declared unfit for military service by reason of poor eyesight. He traveled back to Switzerland, to Wetzikon and then Zurich, where he worked as a watchmaker’s assistant at J. Siegfried and later in the Lansel firm. He lived on the Rindermarkt at that time.

He crisscrossed Germany, wound up on the seacoast and from there he crossed over to North America.

With his years as an assistant completed, Paul Galli needed to think about starting his own business. In 1882, he acquired a small watchmaker’s store on Oberdorfstrasse.

It was just a small, rather dark room with a display window and was so unremarkable that no historical records of it survive. Tradition has the shop situated between Rämisstrasse and Kirchgasse. Oberdorfstrasse in 1900 was a very busy shopping street and its importance faded only with the widening of Bahnhofstrasse. With 500 CHF starting capital, he bought a few used pocket watches that he refurbished and displayed in the store window. That was his entire inventory. His main line of business, however, was not selling watches but repairing them. Since Zurich was a city with a strong contingent of foreign residents including roughly a third who were German citizens, Paul succeeded in quickly building up a loyal clientele.

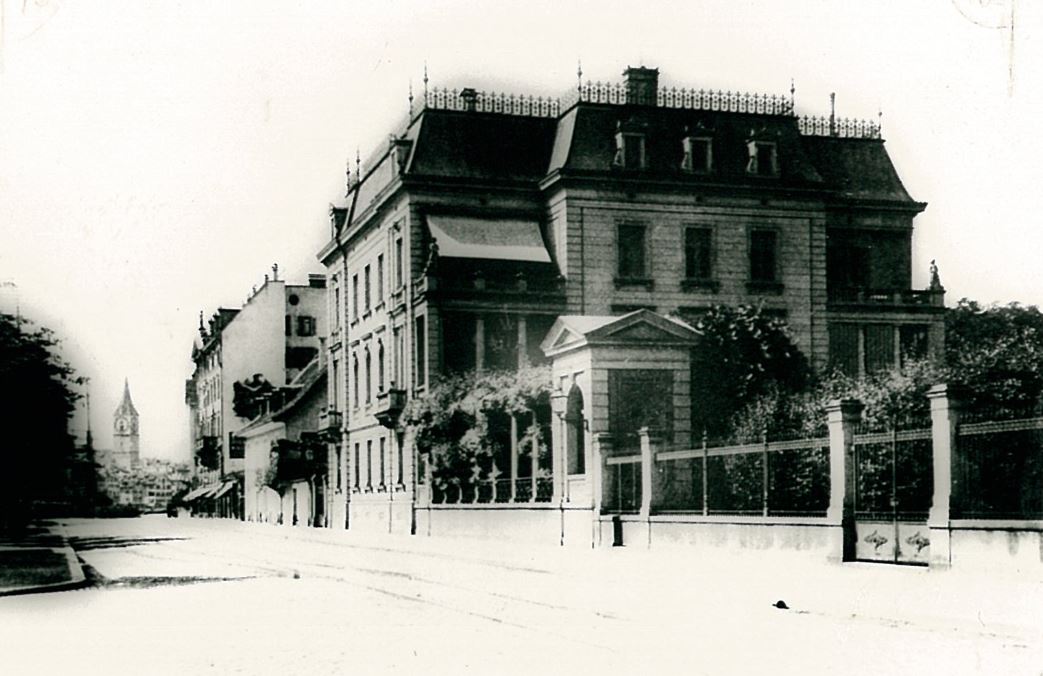

Buoyed by his success, Paul had to find a new store location. He found it on Tonhallenplatz at Tonhallenstrasse 20 – today, Theaterstrasse 20 – and there he set up shop between a cobbler and a cake shop as Horlogerie P. Galli. The store was more spacious than the one on Oberdorfstreet and so, for the first time, he could purchase watches directly from the factory. In those days, the area was not yet part of downtown and the store location was not particularly good, but the view from here was quite beautiful and so the square came to be called Bellevue (“beautiful view.”)

This move marked the start of a new chapter in the expansion and growth of the business. The first priority was on retaining the existing customers and on attracting new ones. Bellevue Square in those days was still completely undeveloped. A few hackneys would be “parked” there, and if people wanted to go somewhere in one, they first had to track down the coachmen in Hinterer or Vorderer Sternen (local restaurants) first. Instead of today’s electric tram, the trams that ran between the main train station over the Limmatquai to the Bellevue and the Tiefenbrunnen, which, by the way, was also founded in 1882, were still horse-drawn. The electric streetcar or tram did not make its debut until the turn of the century. It ran up the Zürichberg from Bellevue to the old Fluntern church and, because of its yellow coat of paint, was also known popularly as the “Flunterner egg crate.” After the country house called “Zum langen Stadelhof,” demolished in 1890, gave way to a new building in 1899, Paul Galli moved in. Galli Watches and Jewelry AG remains in this prominent location to this day.

Before Paul Galli, Theaterstrasse 16 was rented by a master coiffeur Rösler. The annual 1,800 CHF rent had become too much for him and was delinquent. After the move-in, Paul Galli needed furniture. New furniture was too expensive, but fortunately a souvenir shop in the Hotel Bellevue was just then going out of business. Thus, Paul Galli was able to acquire his first store furniture from its proprietor, a Mr. Österreicher-Schüssel. When funds became available in 1905, he ordered his own, brand-new store furniture from the former Hess Carpentry.

The prices that were paid for watches in those days can also be seen in the Galli firm’s catalog. Ladies’ silver pocket watches back then retailed for CHF 18 to 30, with ones in gold already fetching from 30 to 60 CHF. The prices for men’s watches were comparable. Naturally, there was also a price list for repairs and service. Refurbishing and cleaning cost between 4 and 5 CHF, which the clientele considered to be high. Watchmaker salaries ranged from 25 to 30 CHF per week, room and board not included. By comparison, one Otto Seeman, a seller of sausages and seafood in Zurich, charged 1.70 CHF for a pound of Milan salami cost, and lake fish could even be had for 0.30 CHF.

Paul Galli worked tirelessly. As the first watchmaker in Zurich to put electric lights in his display window, he discomfited the competition. He cultivated close connections with the concierges in all the good hotels, who would refer tourists directly to Galli on the Bellevue. Amid success came an enormous setback. All that had been accumulated with 15 years of hard work was lost in just one night, when a gang of thieves looted the entire inventory!

It happened one evening in April, 1897 after the store had closed, as Paul Galli and his wife were still cleaning the store window. It took them until 11 p.m., since stores did not close before 9 p.m. in those days. Tired as they were, they did not lock the watches in the safe as they normally did, and it was that night that they were burglarized. The entire stock of merchandise was stolen, except for items under repair. There was no burglary insurance and so Paul Galli had to start his business all over again.

Contemporary accounts describe the difficult times following the burglary. It was carried out by an Italian gang of thieves, consisting of ten individuals (even including women and children) all taking part in the burglary and fencing of the loot. A few watches turned up in pawnshops in Trento and Verona. Paul Galli traveled there to redeem the watches. Four of the thieves were arrested, and more watches were retrieved from under a fence’s floorboards. Pledging the inventory to the Pawn Office provided liquidity again. As soon as the necessary funds were in hand, the merchandise was redeemed. This was very costly; there was little profit, and a few care- and trouble-filled years ensued.

The business received a boost from the 1900 Paris World’s Fair. This had been preceded by the move from Theaterstrasse 20 to number 16, in time to receive the stream of visitors that materialized after the Paris World Fair. The business was steadily making money again and turned in very good results during the period from 1900 to 1914.

This period also saw attempts at doing business abroad. Very prominent personalities of that era became clients of the P. Galli firm, such as the former Shah of Persia (residing at Baur au Lac) who would eventually buy a gold, diamond-studded man’s pocket watch for 20,000 CHF. The Grand Duchess of Baden, Madame Klinger, and many other famous people are reputed to have been P. Galli clients.

A turning point for the business, 32 years in existence by then, came in 1914 with the outbreak of World War I. All military-age Swiss men were called to arms and all foreigners fled Switzerland in haste. The result was that the business came to a complete standstill during the first six months of the war.

Due to the journeymen’s absence, the watchmaking workshop on Stadelhofenstrasse had to be shut down, never to reopen. Almost every day, passers-by and business people practically snatched the newspapers and special editions from each other’s hands, talked only about the war and were terrified that Switzerland would also be drawn into the calamitous conflict.

The months went by and the business had become a side issue. Fearing the war, numerous property owners throughout the city sold their real estate, and in the midst of this tense situation, his next challenge confronted Paul Galli. The owner of the property at Theaterstrasse 16, Mr. A. Jucker-Huber offered to sell him the property. This gentleman was widely feared and thought of as a brute by those who knew him. The offer was as follows: take it or leave it, you have eight days to make up your mind.

With help from Swiss Bank Corporation, Paul Galli was able to buy the property on October 9, 1915. The fear of war and its consequences was so great that not even one other bidder came to the sale. Paul Galli showed his courage and grabbed it – despite the uncertain economic times prevailing during the 1915 war year.

Prominent personalities of that era became clients of Galli, such as the former Shah of Persia.

Max Galli had his first experience among watchmakers when he was still just a lad, because the watchmaking workshop was housed in his father’s home. This is how he described his “first experience with watchmaking” in the Galli family chronicle: “So as to give me a deep look into the secrets of the trade, one day an assistant let me take a whiff of the ammonium chloride bottle. I could barely breathe and Dora, our domestic, came running in response to my cries. She gave the watchmakers a piece of her mind, and, as for me, I had enough of watchmaking for a while.”

After completing school in Fribourg, Max Galli started his watchmaker apprenticeship in his father’s shop. Although he was never quite sure why he had to learn this trade, for his father Paul Galli it was a foregone conclusion that Max would complete an apprenticeship in watchmaking. Compared with today, it was difficult to obtain spare parts for sold watches, and so replacement parts for repairs had to be made by hand on site.

Max Galli had talent and learned quickly; he could repair not only pocket watches but also large clocks, which became one of his great passions. The big clocks accounted for a large share of sales during the pre-World War I period. Galli was a very active exporter, and watches and clocks would be sent to America or Australia packed in wooden crates.

The second part of his apprenticeship Max Galli spent in Ponts-de-Martel, where he learned to craft fine watches. In keeping with practice back then, there were no pay; instead, the parents had to subsidize the training. In those days, 20 CHF without room or board was a very large sum for his father.

The master was very strict and, of course, the five-day week was still unheard of. Still, Max had many good things to say about this time, because he could spend holidays during his apprenticeship with the family of his boss. They made excursions to France, where15-course meals at the time cost just 2.50 CHF! For his final exam, Max Galli fabricated a man’s pocket watch with minute repetition from raw materials, and, on March 15, 1909, he returned home to the parental business before beginning his assistantship in England.

1914 – 1918

From 1911 on, Max Galli was again working in the father’s business and lived through the difficult war years, when Switzerland was inundated by spies, black-marketeers and speculators. Only Swiss firms were allowed to export goods. In Bern, the export control agency, SSS (Société suisse de surveillance économique) kept a close watch on exports.

As the German currency devalued, legal exports grew ever smaller and only black-marketeers were able to smuggle merchandise into Germany. On one occasion, a batch of watches was bought that could not be paid for with a washtub full of German Marks because they were worth less than the required CHF 10,000 amount due. With war’s end, new worries materialized, for watch sales stopped all at once. All import-export companies, P. Galli included, had excess inventory that they had to sell at a loss.

The price of repairs doubled after the war. Refurbishing a wrist watch no longer cost 10 CHF but 18 CHF instead. A watchmaker at the time made 60 CHF, and the workweek was 54 hours.

1926 – 1972

Our founder Paul Galli passed away on April 29, 1926 in his home, succumbing to pleurisy and meningitis. Now it was Max Galli’s turn to take over the business as the second generation. He had to look after the building as well. In the early 1930s, central heating was installed and an elevator had to be considered as well to make renting the upper floors as office space possible.

On May 20, 1926, the company was transferred to Max Galli. He now had to do the buying, manage the watch workshop and run the business side. He was glad that his father had also sent him to the SKV (Swiss Business Association) business school after his apprenticeship. He implemented a business accounting system for the Galli firm and, using his knowledge, was able to pay his mother for the business in regular installments. He always was on the lookout for new ideas for the business. Repair of automobile clocks was started up; of course, in those days all clocks were still mechanical and had to be wound up or checked regularly.

Max Galli operated a branch store for just a few years at Bahnhofstrasse 78 in Zurich, a location he had taken over from another watchmaker. However, the hoped for business success did not materialize. The crisis years 1930 to 1936 were very difficult. Sales declined year by year and, in 1936, they dropped to the level of what had been a single month’s sales in 1930. This led to the location’s closing in 1939 as World War II broke out.

Helped by the Swiss franc’s devaluation in 1936, the business was slowly recovering. In May, 1939, the National Exposition took place in Zurich. The Galli business was remodeled leading up to this event. The work on the showcases was carried out by Wieland Carpentry, as well as by a family business from Zurich Seefeld, with which the Galli Company still does business today.

Max fell ill during the remodeling and was glad that his wife and the oldest daughter were already active in the business and could direct the work. As he was the president of the ZVSU (Central Association of Swiss Watchmakers), it was his responsibility to set up the watch exhibit at the Swiss National Exposition.

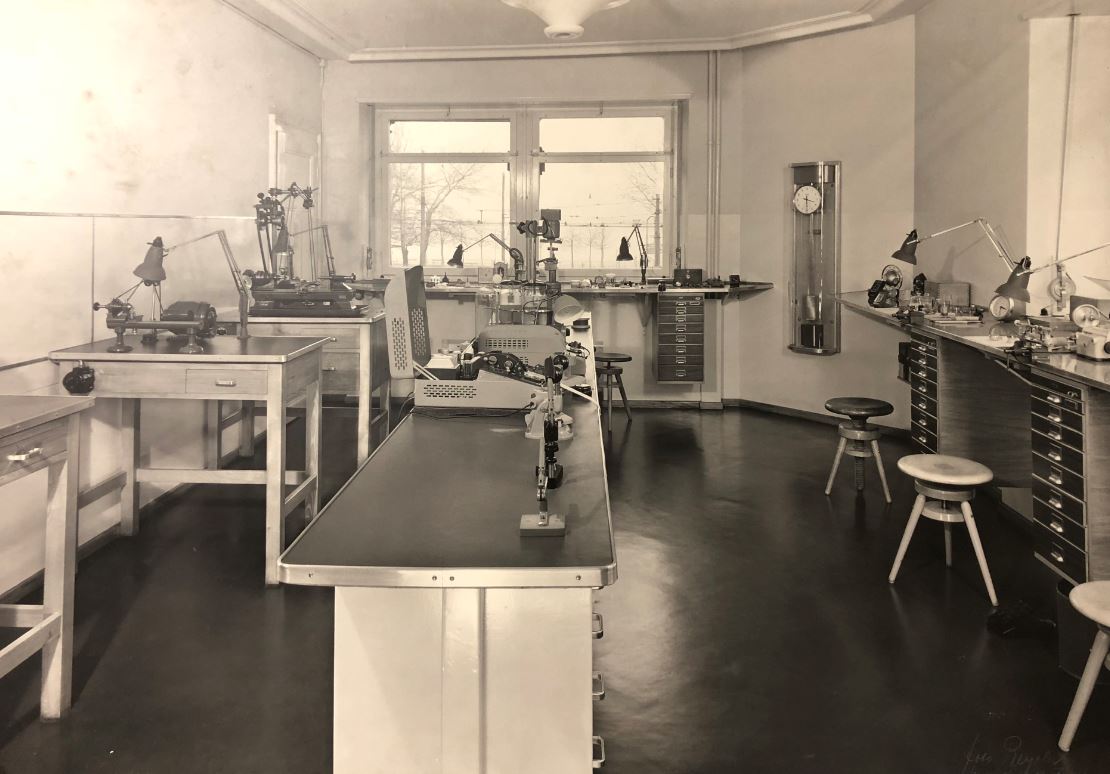

Shortly before this, he had already remodeled his own first floor atelier and hence knew how to set up a modern workshop. A scant nine years later, the store was once again renovated and the exterior façade was also modified. In 1948, they acquired the first car, a Studebaker Regal Deluxe Sedan.

The crisis years 1930 to 1936 were very difficult.

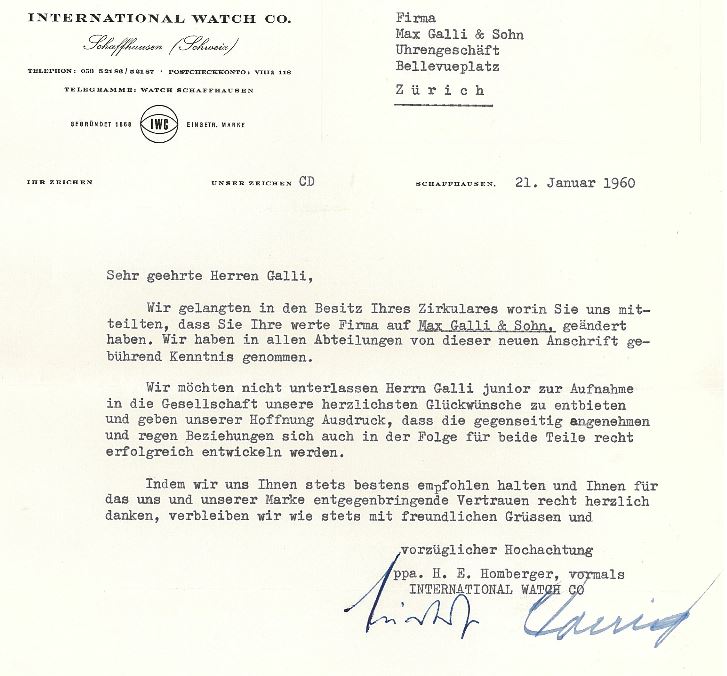

Bruno Galli joined the firm on January 3, 1953, and was made general partner in 1960. The third generation, he also completed a thorough watchmaker’s education at Le Locle where he came in first in his class; his father, as president of the ZVSU, naturally could not have been prouder of son Bruno. He remained at the technical center in Le Locle for some time afterward in order to finish his Tourbillon Marine Chronograph for which he won many prizes. Just like his father, he too suffered from an “eye problem” as a watchmaker and was not drafted into the military, something neither was unhappy about.

Before joining the business, Bruno Galli went to Quebec, Canada for two years to learn English. Then, like his father, he attended the Juventus business school in Zurich. When Bruno joined the business in 1953, it was flourishing and the first employees could be hired. Until that time, only family members had been active in the business, besides the watchmakers. By now, the Galli firm employed three watchmakers and three sales ladies. Sales increased year over year, and so the store location had to be adapted to the boom times.

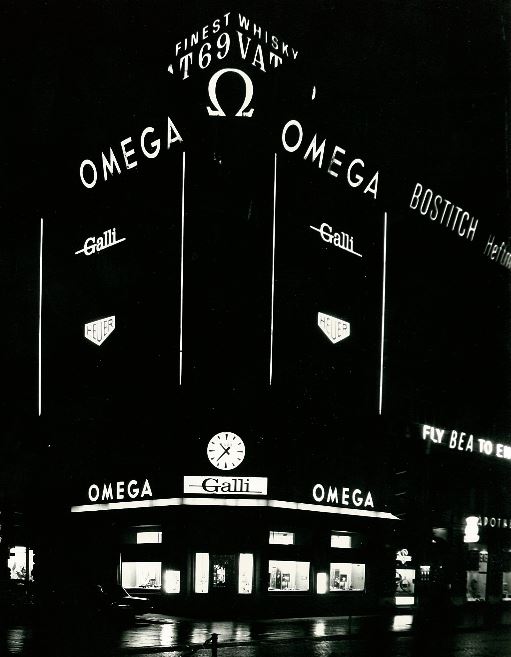

Bellevue Square was no longer regarded as being on the city’s outskirts and the customer base grew steadily. As an attention getter, a canopy was attached to the outer facade and the store was once again renovated in 1958. It was not long before they had outgrown the sales room once more. In 1967, the Forster firm that leased the space behind Galli had to vacate, and the entire lower floor was now turned into sales and office space.

This is how the 150m2 area that is still in use today. Bruno Galli brought many new ideas to the company, and he took full advantage of the emergence of tourist traffic from South America.

All the tour buses stopped directly in front of the Galli store, sales exploded and reached never before achieved levels. This happened when the Swiss watch industry was at its height. At this same time, the Americans landed on the moon for the first time. A Swiss watch was along for the ride: the Omega Speedmaster — the first watch worn on the moon. This model is still sold today at Galli, unchanged, except for the price, which is no longer 595 CHF.

Until that time, only family members had been active in the business.

Sadly, Max Galli died on May 17, 1972, followed only two months later by his son and chief executive Bruno Galli, just 42 years old. Once again, in the history of Galli Watches and Jewelry the future looked bleak. All the traditional work expertise of decades was lost in one stroke, and here stood Nelly Galli, with six children at home and faced with having to make critical decisions concerning Galli’s future on her own.

A quick sale would certainly have kept the family above water for a few years, especially at a bad time for the Swiss watch industry. The previously welcomed foreign groups were staying away and individual travelers could no longer afford the expensive watches. But Nelly Galli showed her courage, stepped into the shoes of Paul, Max and Bruno, and immediately took on all leadership roles in the company. With very generous help from the surrounding businesses, employees, and customers, Nelly Galli was able to guide the company through the great watch crisis. Manufacturers, including Omega and IWC, supported and encouraged Nelly throughout and, in close collaboration, helped Galli maintain its famous standard of service.

Although the bills got paid on time and within discount terms, still every penny had to be counted. Sales during this period collapsed by fifty percent, but Nelly Galli was intent on saving the company to pass it on to the next generation. In 1974, to high inflation was added the oil crisis, which led to “car-free Sundays,” on which only bike travel was allowed on the streets. The watch crisis continued to ripple through the economy, and the number of employees in the watch industry, starting in the early 1970s, shrank from 90,000 to 36,000. But the Swiss watch industry survived, thanks to the team assembled by Nicolas Hayek that merged the ASUAG and SSIH watch companies.

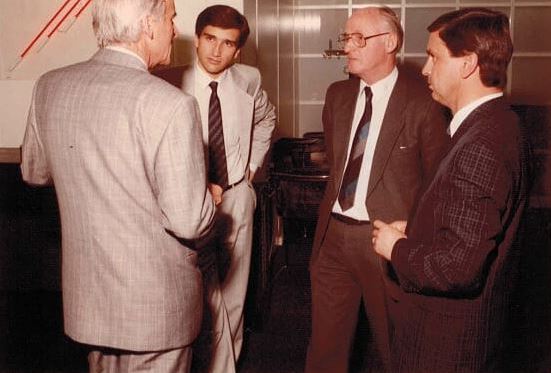

The three Galli generations at a glance. Marco, Nelly and Mario (from left to right).

Nelly Galli was able to guide the company through the great watch crisis.

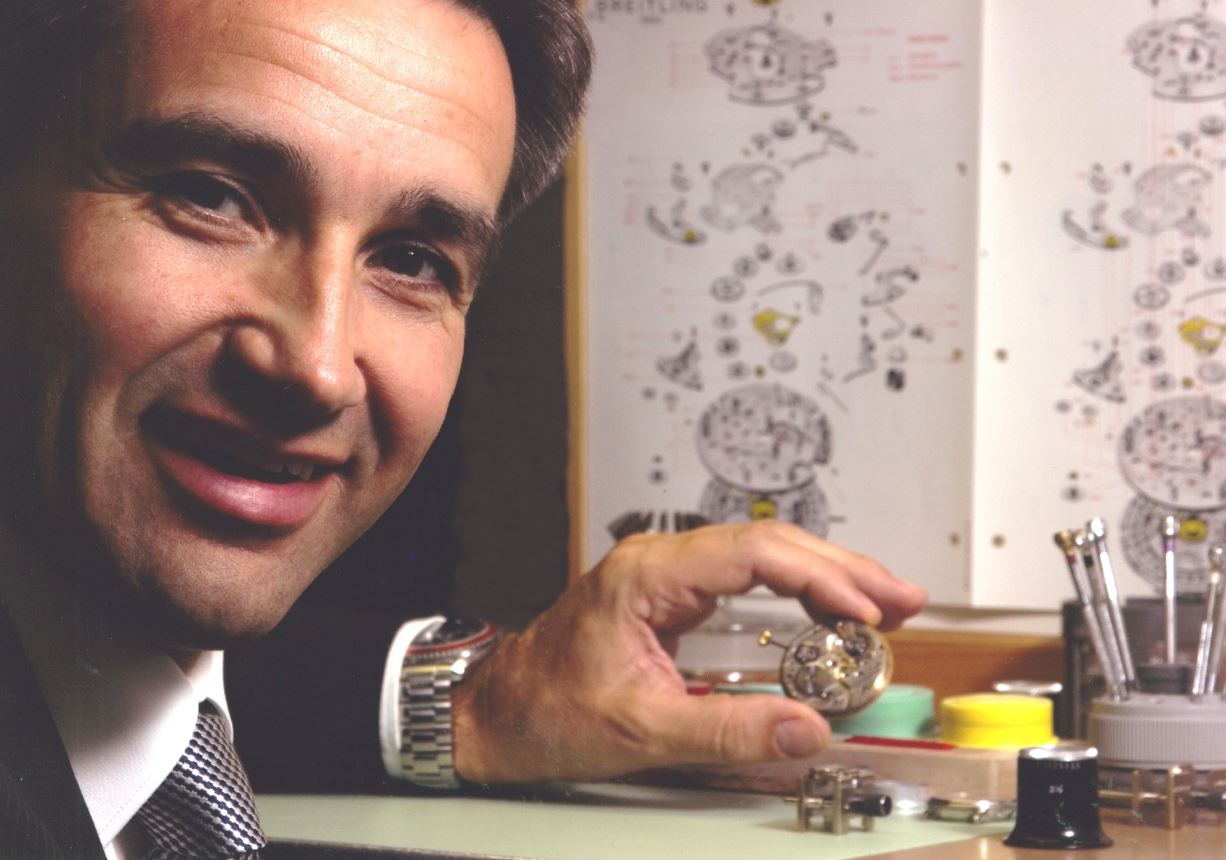

On July 1, 1983, Mario Galli, eldest son of Nelly and Bruno Galli, entered the firm at the age of 24 years and actively supported his mother in its daily operations. Mario had never doubted that he would want to take over the business someday. His father advice to him early on was not to study watchmaking but to get a business education; he himself spent the whole day in the office with hardly any time to apply his watchmaking skills during daily business. Wise words, spoken by his father.

After business school, Mario Galli worked for some time in the banking industry and in the trust business, until his mother Nelly Galli asked him if he was interested in carrying on Galli Watches and Jewelry. The timing was rather unexpected, but Nelly Galli was always clear about her readiness to retire from the company at the opportune time. The decision came quickly. After an internship in the watch industry with “Les Ambassadeurs,” his retraining at CFH in Lausanne was followed by direct entry into the Galli firm. With the watch crisis past, the innovative power of the now fourth generation could be put to work modernizing and changing a few things.

The store was remodeled and the watchmakers’ first floor workshop relocated to the ground floor. After three and a half years of collaboration between mother and son, the company was proudly passed on to the new generation.

In subsequent years, Mario could always count on his mother’s expertise and depend on her for help, particularly during Christmas time. The economy came roaring back, sales increased, and thus not only could the business but also a renovation planned for 1989 be financed. In 1987, the Galli firm took the leap into computers. The revolutionary software used was originally written for hardware stores, but it offered the only possibility for direct data entry at the point of sale register. Everything functioned perfectly, with only the cost of retraining the staff for the digital age coming in higher than Mario had projected.

The watch became a fashion accessory. Revolutionary technology and design by Swatch, Tissot and many other brands invigorated the watch industry sustainably.

With the opening of the Stadelhofen train station, the volume of foot traffic passing the store increased significantly. The new S-Bahn station increased store volume by 30% and made for prosperous times in the Bellevue-Stadelhofen area. When Globus, Orell Füssli and many other big companies moved in, the entire district became more attractive as the skyrocketing rents evidenced.

Fortunately, Galli for generations has been in its own building, passed down by the founder and down from generation to generation. On July 1, 2012, Mario Galli, too, had the chance to take over the Galli part of the property to secure its continued existence for generations to come..

The Galli story continues and, thanks to Mario Galli’s three sons, a fifth generation is waiting in the wings, ready to carry this 125-year old family enterprise forward.

The watch became a fashion accessory.

On the 1st of July 2016 the son of Mario and Ruth Galli, Marco Galli, followed the foot steps of his father. Like Mario Galli he was working in the finance sector and then changed to the watch industry. After some years experience at “Les Ambassadeurs” in Zürich, Geneva and St. Moritz he finished in the year 2015 the Watch Sales Academy in Le Locle. After receiving the federal certificate in watches he was working in the Omega Boutique in Old Bond Street, London.

Marco is looking forward to a bright future of Galli: “In my education I had the chance to get a deep insight into traditional companies. Having a strong connection to regular customers is a must in our business. I am looking forward to be in the 5th generation of Galli and to offer you an excellent service because Galli has time, since over 134 years.”

I am looking forward to be in the 5th generation of Galli and to offer you an excellent service.